The Town Council holds an archive of documents containing a wealth of local history and, thanks to the work of two dedicated volunteers, the archives are being sorted and catalogued for the first time.

Jenny and Mary attend the council offices each week to sift and sort the various files and we are keen to share the information they unearth. This article was prepared by them for the Friends of Knutsford Heritage Centre newsletter when they found an old photo showing men on a stack of hay?

When King Edward VII ascended to the throne after the death of Queen Victoria in 1901 towns and villages began planning extravagant celebrations for his coronation, which was planned for June 1902.

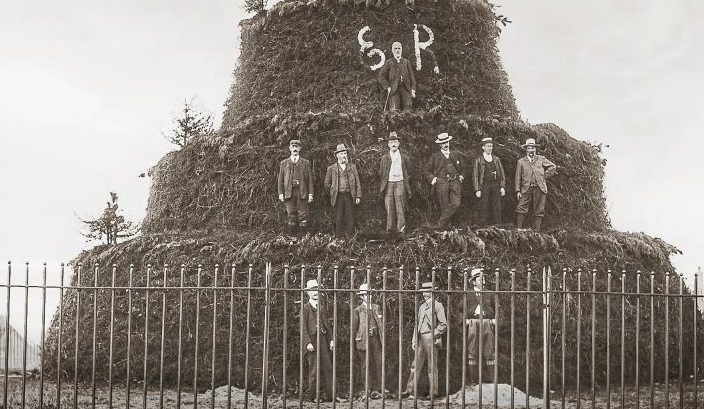

Many towns, including Knutsford, built large bonfires. This photo (which has been skilfully enhanced by Peter Spooner) shows the bonfire on the heath. The men standing on each tier are allegedly the town councillors of the time. You can clearly see a small silver crown near the top and the initials ER.

Knutsford’s bonfire and celebrations are mentioned in George Payne’s ‘A History of Knutsford’, published in 1904:

“On June 26, 1902, the loyal people of Knutsford, besides having a bonfire which measured 52 yards in circumference and was 44 feet high to the floor of the cabin placed on the top, which was itself 10 feet high, had what was quite appropriate, a sanding competition, in which twenty three cottages and tradespeople entered. Most beautiful and artistic designs adorned the street and pavements in front if the houses, and a number of prizes were awarded, the judges touring the ancient streets in a motor car.”

It was also mentioned in other publications, including the Dundee Evening Post, July 1902, which described different bonfires around the realm, accompanied by this illustration and description: “Of quite a different shape was the bonfire at Knutsford, containing 100 loads of stuff. At the base it was 16 yards in diameter, and the blazing properties were heightened by the addition of many barrels of tar.”

The coronation day was set for 26th June 1902 and guests were invited from all over the world. However, the King suffered appendicitis a few days beforehand and developed peritonitis: unless he postponed the

coronation and had an operation immediately he would die. The King, though hugely reluctant, finally relented, and 9th August was chosen as the new date. By then he was much recovered and the service proceeded as planned.

The society magazine “The Queen’ reported at length on regional coronation festivities and in the issue

published a week before the delayed coronation in August, Knutsford gets a special mention:

“There will, no doubt, be many places which will repeat the note of joyousness sounded for June 26 last, when Aug. 9 brings, as we all devoutly hope it may bring, the ceremony that was then postponed. Flags are a possession that can be hung at any moment, and bonfires can be reconstructed, but they will not be either the flags or the bonfires that were prepared when the nation was at the height of loyal expectation.

The little Cheshire town of Knutsford was no whit behind others in its demonstrations of joy; all the customary preparations had been made to honour the King, and another form of decoration, which unfortunately does not show in the photographs, was employed to adorn the pavements of the street. This is the old custom of “sanding”; all the shopkeepers ornament the stone pavement in front of their shops with arabesques, crowns, mottoes, etc. in sand. It is done by putting the sand into a funnel and letting it out in a fine stream, rather in the manner in which a cook ices a cake. The skill that some of them attain is wonderful.

I do not know if the gentle ladies [of Cranford] ever went to any such exciting thing as a bonfire; I imagine they would have thought it slightly improper, but if ever there had been a festivity of that description in their days, certainly Peter, the wicked Peter, who owned to having shot a Cherubim, would have assisted at its making. The photograph somewhat spoilt by the iron railings shows how the bonfire looked the day before the expected Coronation; afterwards, when we lit our bonfires in gratitude that the King was out of danger, this one burnt beautifully, though it canted over in a wonderful way before it was finished, immaculate as it looks here in its resemblance to a gigantic cake.”